Journal of the Bahrain Medical Society

Year 2020, Volume 32, Issue 3, Pages 18-22

https://doi.org/10.26715/jbms.32_2020_3_3Fahad Alqooz1, *, Rana Al Ghatam2

1Resident, Dental & Maxillofacial Department, Royal Medical Services, Kingdom of Bahrain

2Consultant Orthodontist, Dental & Maxillofacial Department, Royal Medical Services, Kingdom of Bahrain

*Corresponding author:

Dr. Fahad Alqooz, Resident, Dental & Maxillofacial Department, Royal Medical Services, Kingdom of Bahrain; Email: Fahad.alqooz@gmail.com

Received date: May 09, 2020; Accepted date: June 28, 2020; Published date: September 30, 2020

Extraction of mandibular third molars is a common procedure that is usually performed in any oral and maxillofacial facility. Pain and dry socket are both common complications encountered. Other related complications include swelling, trismus, and nerve paresthesia. Multiple studies have established the correlation of mandibular molar extractions with specific complications. The aim of the article is to review the evidence relating the complications to the surgery, to understand what a dentist may encounter post-operatively.

Keywords: Complications; Mandibular; Postoperative; Surgery; Third Molar

Globally, mandibular third molar extractions have been one of the most common procedures performed. The complications following this procedure include pain, swelling, trismus, and other iatrogenic complications. Implication of surgery include recurrent infections, presence of a pathology, caries, badly broken teeth, or prevention of mandibular fractures.1,2

Various anatomical structures related to mandibular third molars include the inferior dental nerve, lingual nerve and second molar. Increased incidence of neurosensory problems was reported by Blondeau and Daniel in patients above 24 years of age.1,2 Even though the risk of trauma to the inferior dental nerve is sometimes unavoidable, injury is mostly related to the position of the tooth with regard to the mandibular canal. Inferior dental nerve injury is also a common complication having 96% recovery rates within 4-8 weeks postoperatively.2 A non-surgical extraction is found to be of less impact on the inferior dental nerve than the surgically extracted.2 Hematomas, have also been reported.2,3,4 Postoperative care usually depends on how severe the symptoms are. Food accumulation is a common finding at the extraction site of surgically extracted mandibular third molars which increases the risk of infection.5

Quality of life is mostly compromised due to related postoperative complications Severity of these symptoms differ from patient to patient. Other uncommon injuries include the injury of the lingual nerve.6,7 The learning outcome of the study is to understand the possible complications when extracting mandibular third molars.

Complications are common and differ in their presentations from case to case, depending on the situation. Given below are the common complications related to the extraction of mandibular third molar extraction.

Pain and swelling are the most common features in third molar surgery or any dental extraction, and these factors frequently discourage patients from undergoing dental procedures.5-7 The mechanism is due to the release of pain mediators related to the injured tissues; where these mediators are released as a part of inflammatory process, causing pain and tenderness. The mediators are categorized as vascular and neural. Vascular effects are vascular permeability and vasodilation causing swelling and pain. The neural aspect is subcategorized as activating or sensitizing. Activating types include; potassium, bradykinin, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), serotonin, and histamine. Sensitizing types include; prostaglandins. Leukotrienes, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). 8

Consequent buildup of dental plaque contributes to inflammation thus increasing it. Smoking increases the risk of reduced vascular supply which increases pain itself. 9 Many other factors also influence pain including operator expertise, tobacco smoking, and less commonly the use of oral contraceptive drugs. A randomized split mouth clinical trial compared the postoperative healing in 30 patients who underwent bilateral third molar extraction using either piezoelectric instruments or conventional rotary instruments. After 1 month the sites treated with piezoelectric instruments revealed less periodontal attachment loss distal to the mandibular second and better wound healing.10

Perhaps, postoperative swelling has always been a complication accompanying pain. Postoperative swelling is a result of inflammatory exudate, where an inflammatory response is a normal immune system response to surgical trauma. Several factors seem to influence the incidence of facial swelling and those include; age, gender, fitness and hygiene. Postoperative swelling is difficult to measure and it reaches its highest peak from 24 to 48 hours post-surgery. Swelling can alter daily routine activities of eating or speaking or even socializing.11 [See Figure 1]

Figure 1: Post-operative Swelling

The lingual nerve is a branch of the mandibular nerve of the trigeminal nerve. It lies anterior and medial to the inferior dental nerve.12 Multiple factors contribute to the incidence of lingual nerve injury such as trauma, oral cancer and other routine procedures. Where it has been found that mandibular third molar extractions account for the highest incidence in the injury.13 The location of the lingual nerve was found to be in direct contact with the lingual plate in 62% of the cases in a study conducted in 1984 by Kiesselbach and Chamberlain on dissected cadavers.14 Permanent lingual nerve injury had an estimation of 0.02 to 2% of relative risk in undergoing mandibular third molar extraction. Temporary injuries were documented to an incidence of 0 to 37.5% of patients undergoing third molar surgery. Devoid of a bony canal, lingual nerve recovery is relatively slower than the inferior dental nerve injuries. The use of a magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] was suggested to show the relation of the lingual nerve to the mandibular third molar, but preoperative MRI scan for a minor surgical procedure can be difficult to justify. The incidence of lingual nerve injury was found to be highest in females ranging from 30-50 years having distoangular impaction.15

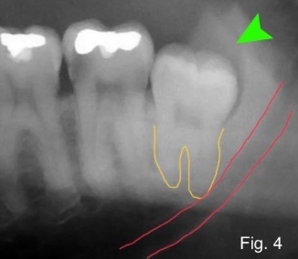

The use of a dentopanoramic tomography [DPT] or a cone-beam computed tomography [CBCT] is improvised in the preoperative assessment relationship between the inferior dental nerve and mandibular third molar.15 [Figure 2-4] Inferior dental nerve injury has been reported to have an incidence 0.41 to 8.1% with temporary damage and incidence of 0.014 to 3.6% permanent damage. Temporary damage is estimated to last approximately 6 months postoperatively. Depending on multiple factors such as; root morphology, tooth position and other anatomical variations. Iatrogenic injuries could possibly be due to crushing of tissues while elevating the involved tooth. The use of local anesthetic has also been implicated in the injuries of the inferior dental nerve and its related paresthesia. 16, 17

Figure 2,3,4: Preoperative assessment relationship between the inferior dental nerve and mandibular third molar

Alveolar osteitis or dry socket on the other hand is a possible complication due to disintegration of the initial blood clots forming inside the socket. Incidence ranges from 1 to 4% with 45% cases related to mandibular third molar.18, 19 The symptoms may vary in onset ranging from 2 to 4 days postoperatively. Symptoms include dull pain, malodor, foul taste, and halitosis.20,21 A study, found incidence to be about 3% of all routine extractions and can be 30% while extracting a mandibular third molar surgically. In another study, it was reported that dry socket ranges from 1 to 5% with 38% being related to mandibular third molars.22

Wound healing is a major factor related to the reduction of any postoperative infection. Another study found incidence of infections to be 3%.23 Infection of the hard and soft tissues is a common complication following extraction of mandibular third molars. It has also been reported that use of a gelatin sponge intra-operatively, can increase the risk of postoperative infections. Nevertheless, it has been observed that delayed infections have a higher incidence than early onset infections.24

The risk of temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) after third molar removal is not found to be elevated statistically for each decade of life. However, the risk may be greater for persons under the age of 21. Younger patients are also more likely to have an impaction of higher severity at the time of removal.25

Mandibular fracture is a very rare complication with an incidence of 0.003% to 0.004%. Fractures may occur intraoperatively, or even postoperatively. As stated by Ethunandan, fractures are presented as case series or case reports. This increases the difficulty in evaluating the risks in relation to mandibular fractures. The same study also observed that the most frequent reason for a fracture is a mesioangular mandibular third molar.26

Maxillofacial procedures have commonly presented with most of the above-mentioned complications. Mandibular third molar extraction is one of the most common procedure any dentist may face. It is considered to be one of the most high-risk procedures present due to its co-morbidities and related complications in oral surgery. Pain, swelling, and trismus are usual outcomes. Other possible complications are less prevalent. Consent should be regularly obtained from a patient prior to any dental procedure due to the increased risks of complications. A verbal consent obtained after educating the patient on the risk of postoperative complications is neither valid nor prudent.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Maximum contribution towards the conception, design, analysis of data and drafting of this manuscript is attributed to the first author, Dr. Fahad AlQooz. All other authors share equal effort contribution towards (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the manuscript version to be published.